(Submitted by Overseas Security Advisory Council)

Digital contact-tracing mobile applications have become a useful mitigation tool for countries and private-sector organizations alike in the fight against COVID-19. South Korea and Singapore were among the first to deploy a digital version of contact tracing, a key reason those countries have experienced relatively few coronavirus cases. In the United States, such measures have fallen largely to tech companies, resulting in a rare partnership between Apple and Google to develop contact-tracing technology that will operate on both iOS and Android phones. However, other countries have implemented apps that raise serious security concerns for private sector operators. This report looks at the issue as a whole, and examines its implications in two key countries for OSAC members.

Using Contact Tracing Applications

While governments and major companies work to create and monitor tracing apps, private sector organizations have also begun acquiring mobile applications and wearable devices to track and stop the spread of coronavirus in the workplace. PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), which is building its own contact tracing app, noted that nearly a quarter of chief financial officers they surveyed plan to evaluate the technology as part of an office reopening strategy. A recent survey of 300 OSAC members received similar results; 22% of respondents noted that their organization was considering the use of contact tracing mobile applications to identify and track possible COVID-19 infections, with another 3% reporting that their organization was already using these applications. These responses were highest in Asia, where almost 30% of respondents reported either considering or currently using contact tracing mobile applications.

As organizations consider mandating these technologies in the workplace, many questions arise such as whether participation actually makes employees safer (or just feel so), if apps are legal and appropriate to deploy and mandate for employees, and if the technology will work as advertised in the field. The legality and appropriateness of mandated digital contact tracing in the workplace is likely to differ by country and organization. Also, organizations may need more time and experience to fully understand how well the technology will work, and how it will impact employee safety. Regardless, the mandated use of these technologies present cybersecurity and privacy concerns that can and should be examined before considering or committing to any new platform.

GPS vs Bluetooth

The two primary forms of digital contact tracing mobile applications are those that rely on GPS and those that use Bluetooth. GPS-based apps, such as those in South Korea and Israel, are the most intrusive on privacy, since they track and communicate user locations and movements to a centralized source (like the government). They can pinpoint potential locations of exposure, as well as the phones of the users who appear to have been in close contact with an individual. Meanwhile, those that rely on Bluetooth technology, like the apps in Singapore and Australia, can tell you when you might have been exposed to COVID-19, but they are more decentralized and will not tell a user where or to whom they were exposed. Privacy advocates prefer the latter for these reasons. Some legal experts argue that the optimal design for private-sector organizations from a privacy point of view leverages Bluetooth technology without giving the employer access to the server containing the information.

Companies Behind the Apps

In addition to understanding the technical backbone on which these applications rest, organizations should also consider the developers and their track records with cybersecurity and privacy issues. There is a wide variety of companies seeking to develop this technology and earn their share of what may prove to be a lucrative market moving forward. These include all types of organizations, from traditional business software and professional services companies like PwC and Salesforce, to technology startups and cyber intelligence firms.

According to Reuters, at least eight surveillance and cyber-intelligence companies are attempting to sell re-purposed spy and law enforcement tools to track COVID-19 and enforce quarantines. Executives at four of those companies said they are piloting or in the process of installing products to counter coronavirus in more than a dozen countries in Latin America, Europe, and Asia.

One of the more controversial companies in this group is the Israel-based cyber intelligence firm, NSO Group. The surveillance software-developer is currently being sued by WhatsApp for allegedly helping governments hack 1,400 targets, to include activists, journalists, diplomats, and state officials using its signature software, Pegasus. The company also faces another lawsuit in which it is accused of supplying software to the Saudi Arabian government, which allegedly used it to spy on the journalist Jamal Khashoggi before his murder.

While these platforms, which largely rely on GPS location data, have primarily marketed to governments, organizations interested in employing digital contact tracing tools within their facilities and workforce should also be wary of clandestine technologies traditionally used for surveillance. Beyond the damage that such technologies could cause to an organization’s business image or employee trust, they could also present significant data privacy concerns, depending on how the data is collected, stored, and accessed. Organizations should also monitor which countries are adopting these more privacy-invasive technologies, as countries more predisposed to dissent suppression and other digital authoritarian practices could easily abuse then.

Two Significant Case Studies

OSAC has received inquiries from the private sector regarding digital contact tracing apps that host governments are mandating for employees. According to MIT Technology Review’ COVID-19 Tracing Tracker, 25 countries currently have significant automated contact tracing efforts in place, and five of those countries (Bahrain, China, India, Qatar and Turkey) mandate use of tool . Two case studies address how mandated use might impact U.S. private-sector employees operating in the world’s two most populous countries.

China

Color-Coded Health Passes

China has rolled out a color-coded health system based on travel history and contact tracing to monitor new COVID outbreaks. While downloading the app is not mandatory, the health code is necessary to enter public places such as public transportation, residential compounds, hospitals, workplaces, or schools, or to travel domestically. If an individual has not been in an area with a recent breakout, they will receive a green code indicating that they are likely healthy. A yellow or red code can restrict them from daily activities and force them to quarantine in a government facility or self-isolate at home.

The COVID App

The predominant COVID-19 tracking app is not a stand-alone app, but rather integrates into WeChat or AliPay as a ‘mini app.’ Users scan a QR code on their app to enter public spaces. The color code generates based on location-sharing data on the phone. WeChat and AliPay are nearly essential to daily life in China. The popular apps combine texting, calling, social media, and credit cards, and make it easy to download the COVID attachment. Those who do not wish to use the app can also enter a Chinese phone number, which will also communicate information on a person’s recent travel history. One potential concern regarding enforcement are reports that WeChat check-ins may be mandatory, meaning just entering a Chinese phone number would not be enough. At the moment, it is not mandatory for private organizations to request health code scans for those entering their premises, but the government highly encourages the practice, and organizations are responsible for having a plan to defend against the virus. Businesses do have the authority to refuse entry to anyone who will not show their health pass. Most preventative coronavirus measures in China are implemented at the local level. Enforcement and use of the app varies widely.

Security Concerns

China’s surveillance apparatus poses a security concern for the private sector on many levels. Government surveillance is highly integrated into many private products. Both WeChat and AliPay are platforms developed for the Chinese government and are known conduits of personal information to the Chinese government – although their ubiquity means most people have agreed to the trade-off of privacy for ease. The Chinese government already has the ability to track anyone who has downloaded the apps to their phone, or who has a Chinese phone number. The add-on does not present additional security concerns.

A Permanent Health App

While many recognize the need for extra precautions to slow the pandemic, some fear the government may expand the apps into a permanent tracker, which could present even more serious privacy concerns than the current state surveillance system. This fear is not without basis. While there is not yet an announced central government plan for a permanent health tracker, Hangzhou, the city where the tracking app first launched, has announced such an initiative for its population of over 10 million.

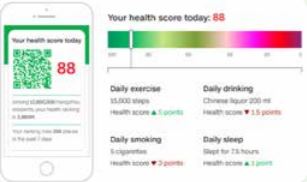

The proposed health app would monitor an individual’s health based on medical records, activity levels, hours slept, and other lifestyle choices including smoking and drinking. The current COVID app has three color codes, but the new one is a combination of a rainbow color code and a ranking from 1-100. The commission’s director also proposed a composite group health score for private-sector organizations. Chinese citizens have been outspoken against the permanent app. They have expressed concern that making private health records public could be a serious issue, possibly affecting insurance premiums and job opportunities. Without addressing these concerns, the city has stated that the app will be ready by the end of June.

A permanent health app could have further societal implications if it mimics or feeds into China’s social credit system. The social credit system proposes ranking citizens and punishing them for bad behaviors like jaywalking or buying too many video games. Individuals need good social credit to participate in various activities from traveling on high speed trains to enrolling kids in good schools. If the government implemented a health app in a similar way, it could have serious societal consequences.

India

Aarogya Setu

The Government of India released the contact tracing app Aarogya Setu (Hindi for ‘a bridge to health’) in early April. The app already has nearly 100 million users, making it one of the fastest-downloaded apps ever. The contact tracing app is a massive undertaking that tracks Bluetooth contact events and location, and gives each app user a color – coded badge showing infection risk. Aarogya Setu requires constant access to Bluetooth and data, raising significant concerns over privacy, government surveillance, and enforcement mechanisms across private industry. India lacks a federal data privacy law, making it unclear who has access to data from the app, and what limitations, if any, exist. The list of the app’s developers is not entirely public. The app’s founders have stressed that it was built to the standards of a draft data privacy bill currently in India’s parliament, and that access to the data it collects is controlled.

Enforcement

At first, use of Aarogya Setu appeared voluntary, but the government has since mandated its use for central government employees. This trend is part of a known ‘voluntary-mandatory’ tactic for emerging technology in India. While enforcement on downloading the app is technically still voluntary, private employers have followed federal mandates with their own orders for employees to download it. Sources in the smartphone industry are reporting that Indian officials have asked smartphone makers to pre-install the app on all devices, though this is not yet confirmed.

Enforcement of app use across private industry has fluctuated. Stories have emerged about landlords and property managers requiring residents to download the app, and pharmacies denying entry to individuals without the app. Food delivery services in India, including gigworker apps, have made it mandatory for their employees, mostly as part of the country’s guidelines allowing e-commerce firms to function during the nationwide lockdown. Passengers on the New Delhi metro may have to have the app once the lines reopen. Government officials have also proposed making the app compulsory to travel by air. In its limited reopening of 15 special train lines, Indian Railways announced that it would mandate the app for all passengers. In Noida, a city on the outskirts of New Delhi, police have ordered residents to install the app or face detainment and punishment. Senior police officers have advised officers to conduct random checks on roads and at state borders to ensure app installation.

Security Concerns

I n addition to concerns over the absence of a federal data privacy law, the app itself may present security vulnerabilities to users. An independent security researcher found that one feature of Aarogya Setu, designed to let users check if there are infected individuals nearby, instead allows them to spoof their GPS location and learn how many people are reportedly infected within any 500-meter radius. Hackers may even be able to use a so-called triangulation attack to confirm the diagnosis of someone who they suspect is infected. The use of GPS data in addition to Bluetooth may represent a cautionary tale about serious leaks of sensitive medical information.

To assuage concerns over data privacy, the Indian government released a set of guidelines about how Aarogya Setu collects and uses data. The guidelines claim that data collected through the app is anonymized and only used ‘for COVID-19 related purposes,’ but doesn’t contain much further detail. The guidelines also state that captured data can only be retained for 180 days, and will be deleted after a certain period of time for healthy and infected individuals. Founders of the app are still attempting to work within the framework for contract-tracing apps introduced by Apple and Google, whose coding methods have not allowed access to location services or use of data for advertising, both of which Aarogya Setu uses. One positive development for data privacy activists materialized recently, when the Government of India announced it would be making the source code of Aarogya Setu public and accessible by open source.

Where to From Here?

COVID tracking apps can be extremely helpful in containing the virus and lowering a country’s new case rate. However, there are also serious security concerns for businesses and members of the public especially in countries that essentially require tracking regardless of residency. Employees can take steps to minimize risks in several ways:

- Only download the apps on personal phones rather than company phones.

- Use a burner phone with a local number to enter public spaces.

- When leaving a foreign country, delete the app.

These tracking apps are new and varied, it may be that companies and governments may be able to engage with consumer criticism to create better privacy barriers in the future. In the meantime, users can focus on minimizing security threats while still contributing to public health.